On Collaboration, Imitation and Genius in Art

On the outskirts of Shenzhen is Dafen artists village — a square kilometre of tangled alleys entirely dedicated to oil painting.

Once responsible for an estimated 60% of the world’s oil painting output, families of artists crowd the small alleys to churn out countless copies of Sunflowers and The Starry Night.

Each artist is responsible for specific elements in a piece — the more skilled artists working on more intricate details. Walking amongst the alleys, unfinished paintings are passed from easel to easel. To be updated and augmented.

This factory approach is by no means unique to Dafen — though perhaps here it is most transparent.

Lots of Sunflowers

“Painting is the silence of thought and the music of sight.”

― Orhan Pamuk, My Name is Red

Thangkas, the Tibetan Buddhist paintings so readily available in Kathmandu and Lhasa are sold as works of intense mastery by individual monks. In reality, most of the less expensive thangkas are painted by teams of painters working on the outskirts of Kathmandu.

In My Name is Red, Orhan Pamuk sets his meta-fiction love story within the workshop of Ottoman miniaturists.

Thangka shop in Thamel, Kathmandu

These religious artworks were usually not signed — perhaps because of the rejection of individualism, but also because the works were not created entirely by one person. Typically, the head painter designed the composition of the scene, and apprentices drew the contours with black or coloured ink and then painted the miniature.

“Where there is true art and genuine virtuosity the artist can paint an incomparable masterpiece without leaving even a trace of his identity.”

― Orhan Pamuk, My Name is Red

But our geniuses do otherwise.

In the West, we are obsessed with the idea of artists as creative genius. An individual. A unique talent who far surpasses us mere mortals, who singularly conjures up works of incomprehensible mastery in a vacuum.

Artists like Leonardo da Vinci.

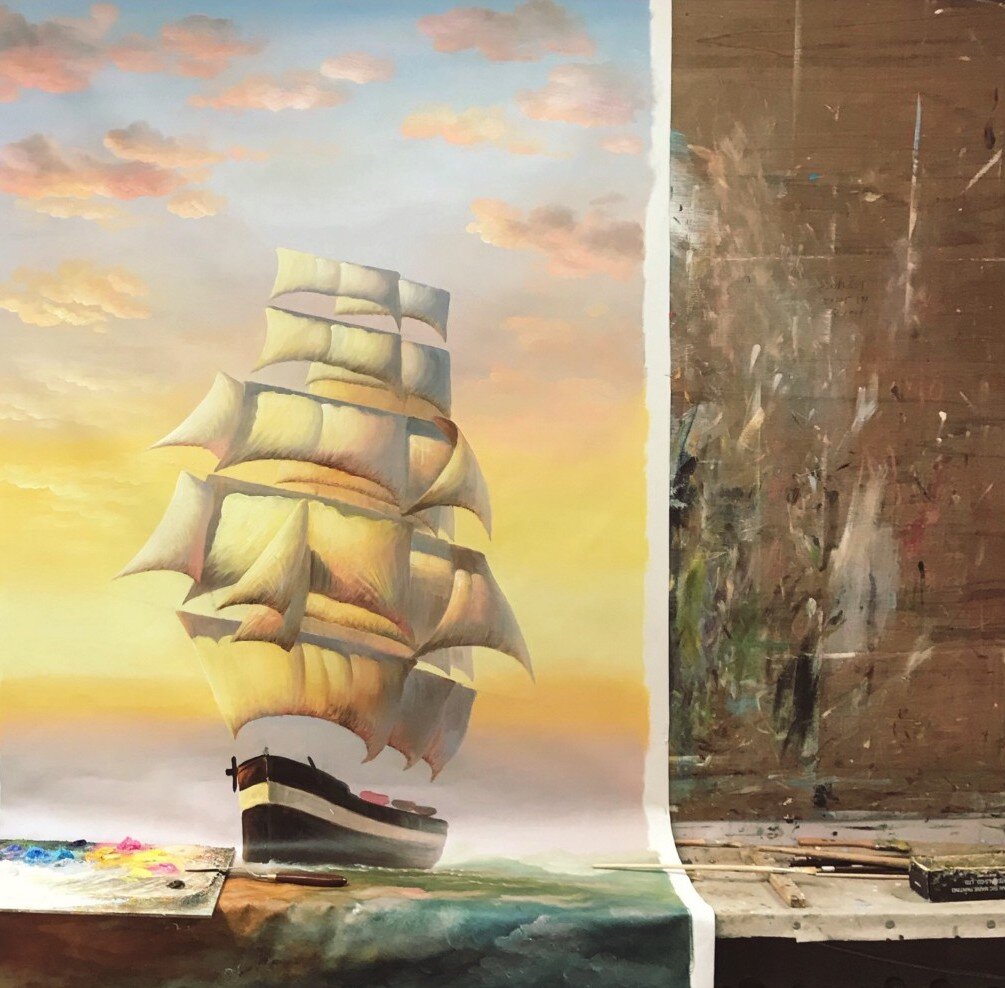

Floating sails, Dafen, Shenzhen

Obsessed is perhaps not quite the right word; we are not preoccupied with the idea of individual creative genius. We simply assume it. We learn the names of the great Renaissance painters — but rarely their working environment and collaborators.

Leonardo learned his trade in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio — here the goal was to produce a constant flow of marketable art and artifacts rather than to nurture creative geniuses with works of unparalleled originality. Many of the works were collaborative pieces produced as if on the production lines of Dafen’s alleyways.

And so it was when Leonardo set up his own studio. Leonardo would create the compositions, sketches, and studies. His students would copy them and work as a team on the finished version, with Leonardo adding his own touches and making corrections.

There’s no doubting the genius of Leonardo. Yet our assumptions of how he worked are far from accurate.

The imitation game

Made in China 2025 is a strategic plan by the Chinese government to move its industries up the value chain, away from outsourced manufacturing and toward design— to return to a time when the West copied its creative industries.

Many of the artists and investors in Dafen pursue this goal also — already there are independent galleries and cafes sprinkled amongst the the more traditional workshops. Dafen is beginning to position itself as an authentic creative hub. A place for original art and culture.

Imitation is not only the greatest form of flattery. But a great place to begin the ascent to mastery. All the better if you can do it in a team.

Spotted in Shenzhen, China.